To be successful, a populist demagogue has to project belief in himself as a man of destiny. Self-obsession and even megalomania help; they may well be essential. In a compelling book, Disordered Minds, the Irish writer Ian Hughes suggests such men are narcissists or psychopaths. To a non-expert eye, they do appear deranged. How else can one sell the idea that “I alone am the people’s salvation” to oneself?

If such a leader wishes to subvert democracy, it is, alas, not that hard to do, as Harvard’s Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt argue in How Democracies Die. First, capture the referees (the judiciary, tax authorities, intelligence agencies and law enforcement). Second, sideline or eliminate political opponents and, above all, the media. Third, subvert the electoral rules. Supporting these assaults will be a fierce insistence on the illegitimacy of the opposition and the “fakeness” of information that does not align with whatever the leader finds useful to state.

People will want to trust such a leader whenever they desperately wish to believe that someone powerful is on their side in an unjust world. That is what happens when trust in the institutions and norms of a complex democracy falters. When faith in sober policymaking disappears, the charismatic figure emerges as the oldest kind of leader of all: the tribal chieftain. When things become this elementary, the difference between developing and so-called advanced democracies can well melt away. True, the latter have stronger institutions and norms and a more educated electorate. In normal circumstances, that may be enough to resist. Some argue it will remain enough. Yet, we are human. Humans adore charismatic despots; they always have.

24 d’abril 2019

Succesful populists: the age of elected despots

These are selected paragraphs from Martin Wolf excellent op-ed Elected despots feed off our fear and rage:

21 d’abril 2019

Theranos details explained: the "inventor" that fooled so many smart people

The Inventor: Out for Blood in Silicon Valley (2019)

Former posts have explained the story, now a 2h. HBO documentary adds details:

Former posts have explained the story, now a 2h. HBO documentary adds details:

19 d’abril 2019

On the effectiveness of digital health technologies

EVIDENCE STANDARDS FRAMEWORK FOR DIGITAL HEALTH TECHNOLOGIES

Every other day we here about a new health app, and new digital advances in healthcare. Too often, any innovation is considered effective without any deep analysis. Now, NICE provides a guide for this specific issue.

Every other day we here about a new health app, and new digital advances in healthcare. Too often, any innovation is considered effective without any deep analysis. Now, NICE provides a guide for this specific issue.

The economic impact of a DHT can be assessed using an appropriate analysis of the economic information collected. The type of economic analysis done should be determined by the financial consequences of adopting and implementing the DHT from a payer or commissioner perspective. The appropriate level of economic analysis depends on the type of decision needed and likely financial commitment. To reflect the range of commissioning decisions associated with DHTs, we have proposed 3 levels of economic analysis (see table 8).

Many DHTs will start at a basic economic analysis level but, with additional information and data about the technology and its comparators, a more robust economic analysis can be undertaken. The higher levels of economic analysis needed depends on the financial commitment required including, for example, the level of upfront investment, the likelihood of opportunity costs and the certainty of the realisation of the benefits.

18 d’abril 2019

17 d’abril 2019

AI in healthcare, a podcast

How A.I. Is Humanizing Healthcare with Dr. Eric Topol

Can A.I. and machine learning make healthcare more humane, loving, and passionate?

Dr. Eric Topol thinks so.

Dr. Topol (Website | Twitter) is a geneticist, medical researcher, and author of Deep Medicine. He has written over 1100 peer-reviewed articles and is one of the top most-cited medical researchers in the world.

In this episode, Chad sits down with Dr. Topol to talk about how A.I. and machine learning are putting the patient experience back at the forefront of healthcare. Dr. Topol also explains why you don’t actually own your own medical data and what steps we need to take to get it back.

Can A.I. and machine learning make healthcare more humane, loving, and passionate?

Dr. Eric Topol thinks so.

Dr. Topol (Website | Twitter) is a geneticist, medical researcher, and author of Deep Medicine. He has written over 1100 peer-reviewed articles and is one of the top most-cited medical researchers in the world.

In this episode, Chad sits down with Dr. Topol to talk about how A.I. and machine learning are putting the patient experience back at the forefront of healthcare. Dr. Topol also explains why you don’t actually own your own medical data and what steps we need to take to get it back.

09 d’abril 2019

A lifetime fair drug pricing system

When Is The Price Of A Drug Unjust? The Average Lifetime Earnings Standard

Is there any measure for unfair pricing in drugs?. According to Ezequiel Emanuel prices should not

Is there any measure for unfair pricing in drugs?. According to Ezequiel Emanuel prices should not

"exceed 11 percent of the average American’s disposable income. This suggests that current prices for many drugs are excessive and unjust."Why?.

Currently, average lifetime costs for health care are estimated at 31 percent of disposable income. Drugs account for 17 percent of health care expenses. A threshold for medical care as a share of disposable income that is set 10 percentage points higher than the current average amount spent on medical care (at 41 percent, or $261,907) is generous, as is a threshold for drug costs as a share of medical costs set 10 percentage points higher (at 27 percent, or $70,715) than the current share. Using these standards, the costs for all of the drugs a person takes in a lifetime should not consume more than 27 percent of medical costs, or $70,715. This constitutes 11 percent of lifetime disposable income.He achieves this conclusion after applying these principles:

1. Complete life. The unit of analysis should not be a year or other limited time frame, but rather the impact over a whole lifetimeThis article represents a deep change of perspective on drug pricing. Cost-effectiveness of individual drugs are not enough, a lifetime and societal perspective is necessary. I agree in this part, however methodological implications are huge and uncertain.

2. Limited resources. The just price of a drug should reserve enough resources for people to pursue valuable life activities

3. Value. There should exist a close relationship between the actual benefits of an intervention and its price

4. Comprehensiveness. Life activities other than health matter; in considering the benefits of a treatment, we should also consider how it affects education, employment, and other valuable life activities

Bonnard at Tate modern right now

05 d’abril 2019

Personal Health Data Cooperatives

Personal Data Cooperatives – A New Data Governance Framework for Data Donation and Precision Health

The Ethics of Medical Data Donation

The Ethics of Medical Data Donation

Given that personal data can be copied, individuals are entitled to copies of their data and individuals are the ultimate aggregators of all their personal data, citizens are elevated to new roles at the center of health research and a novel personal data economy. There, citizens, not some multinational company, control the use of and benefit from the intellectual and economic value of these data.In a chapter of the book you'll find a description of MIDATA cooperative, a swiss case. My impression is that this is the appropriate approach. A closer initiative is SalusCoop. However, as happens in any public good, its governance is always the foremost issue.

03 d’abril 2019

01 d’abril 2019

30 de març 2019

Medicine as a data science (6)

Adapting to Artificial Intelligence: Radiologists and Pathologists as Information Specialists

While some physicians are lobbying for creating more specialties, Jah and Topol argue exactly the opposite. Radiology, pathology and in vitro diagnostics should be under the same umbrella: "the information specialists":

While some physicians are lobbying for creating more specialties, Jah and Topol argue exactly the opposite. Radiology, pathology and in vitro diagnostics should be under the same umbrella: "the information specialists":

Because pathology and radiology have a similar past and a common destiny,

perhaps these specialties should be mergedinto a single entity, the “information specialist,” whose responsibility will not be so much to extract information from images and histology but to manage the information extracted by artificial intelligence in the clinical context of the patient.

There may be resistance to merging 2 distinct medical specialties, each of which has unique pedagogy, tradition, accreditation,and reimbursement.However, artificial intelligence will change these diagnostic fields. The merger is a natural fusion of human talent and artificial intelligence. United, radiologists and pathologists can thrive with the rise of artificial intelligence.

The history of automation in the broader economy has a reassuring message. Jobs are not lost; rather, roles are redefined; humans are displaced to tasks needing a human element. Radiologists and pathologists need not fear artificial intelligence but rather must adapt incrementally to artificial intelligence, retaining their own services for cognitively challenging tasks.A unified discipline, information specialists would best be able to captain artificial intelligence and guide medical information to improve patient care.You may agree or not. Technology is breaking barriers and creating bridges. Food for thought.

Josep Segú - Brooklyn Bridge

27 de març 2019

The deep side of medicine and the gift of time

Deep Medicine

Nowadays the impact of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine is unknown. Every other day you may hear about robots and how they will replace humans. Nobody knows about it, distrust charlatans. The only thing that is real is what is already happening. Eric Topol has tried to do this in his new book Deep Medicine. But at the same time he considers that AI will let physicians humanise medicine, "the gift of time", and says:

The remaining elements of the book are of interest to explain the current state of advances in apps and tools for clinical decision making. You'll find helpful information and a great summary of AI in medicine. However, my suggestion is that you can forget the subtitle of the book: "How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again". It's naïve.

Nowadays the impact of Artificial Intelligence in Medicine is unknown. Every other day you may hear about robots and how they will replace humans. Nobody knows about it, distrust charlatans. The only thing that is real is what is already happening. Eric Topol has tried to do this in his new book Deep Medicine. But at the same time he considers that AI will let physicians humanise medicine, "the gift of time", and says:

"As machines get smarter, humans will need to evolve along a different path from machines and become more humane"This may be Eric Topol's desire, nothing to add. My view is quite different. I'm not sure about the contribution of AI to a humanised medicine . This has to do with professionalism, not with AI. And the incentives for professionalism are plunging, while commercialism is on the rise. This is the key issue.

The remaining elements of the book are of interest to explain the current state of advances in apps and tools for clinical decision making. You'll find helpful information and a great summary of AI in medicine. However, my suggestion is that you can forget the subtitle of the book: "How artificial intelligence can make healthcare human again". It's naïve.

22 de març 2019

The Theranos contretemps as a serious scandal (2)

The DropoutPodcast by ABC Radio & ABC News Nightline

The inventor

Now you can hear the ABC radio podcast in 6 chapters on Theranos scandal. Report at The Verge. Highly recommended.

And the HBO new documentary explains all the details in 2 hours. The trailer:

The inventor

Now you can hear the ABC radio podcast in 6 chapters on Theranos scandal. Report at The Verge. Highly recommended.

And the HBO new documentary explains all the details in 2 hours. The trailer:

20 de març 2019

#CRISPRWHO: notes on a new scandal

Open AccessOpen Access license

#CRISPRbabies: Notes on a ScandalThis week:

An advisory panel to the World Health Organization has called for the creation of a global registry to monitor gene-editing research in humans, the organization announced yesterday (March 19). The recommendations of the 18-person committee, which was established following news late last year that Chinese scientist He Jiankui had carried out human gene editing in secret, are aimed at improving transparency and responsibility in the field, the announcement says.

The panel’s advice did not go so far as to call for a moratorium on all human germline editing, unlike some other groups. Last week, a group of scientists and bioethicists from seven countries penned a commentary in Nature that argued for “a fixed period during which no clinical uses of germline editing whatsoever are allowed.” Such a moratorium would allow time for ethical and moral debate and for the agreement of an international regulatory framework, they wrote.After the initial #CRISPRbabies scandal , we are facing a new one. The WHO pannel is asking for a registry instead of a moratorium. The battle has finished. Game over. From now on, the human being will be affected from such decision. One of the worst decisions in the human history.

17 de març 2019

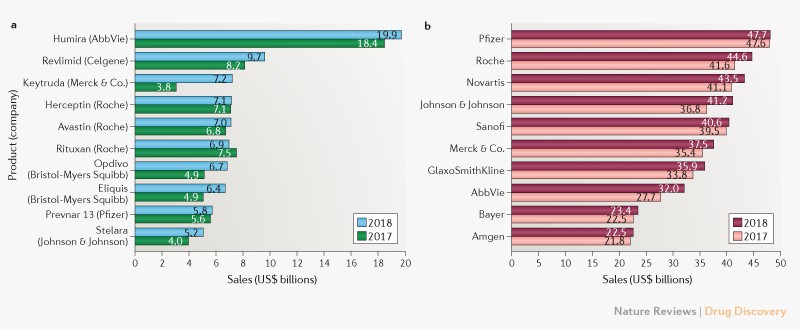

Improving the pharmaceutical regulation production function

Using Routinely Collected Data to Inform Pharmaceutical Policies

With the broadening of data available for officials to regulate markets, things could change. The issue is specially relevant for pharmaceuticals. Up to now if you want information about the market you have to use IMS data. Now governments that pay the drugs bill can use their own data to improve regulation. Better knowledge could represent better regulation if it is performed appropriately and on a timely basis. The OECD report tries to put all these elements together and highlight the opportunities ahead.

With the broadening of data available for officials to regulate markets, things could change. The issue is specially relevant for pharmaceuticals. Up to now if you want information about the market you have to use IMS data. Now governments that pay the drugs bill can use their own data to improve regulation. Better knowledge could represent better regulation if it is performed appropriately and on a timely basis. The OECD report tries to put all these elements together and highlight the opportunities ahead.

This report provides an overview of patient-level data on medicines routinely collected in health systems from administrative sources, e.g. pharmacy records, electronic health records and insurance claims. In total 26 OECD and EU member countries responded to a survey addressing the availability and accessibility of routinely collected data on medicines and their applicability to developing evidence. The report further explores the utility of evidence from clinical practice, looking at experiences and initiatives across the OECD and EU.Governments will have to improve big data capabilities and add new talent.

Subscriure's a:

Missatges (Atom)