Un amic em pregunta: Sincerament, vista la situació incerta que vivim, què caldria fer com a país per millorar el benestar dels ciutadans?. Jo li contesto que això requereix un llibre sencer. I afegeixo, abans de fixar uns objectius de futur, cal estar segur del diagnòstic, cal saber on som. Hi ha gent que no sap a quin país viu, i d'altres que ni ho volen saber i que tant sols es troben en un territori. Cal que els governants sàpiguen quin és el país real que han de governar. I afegeixo, he constatat que massa sovint els decisors públics s'imaginen un país inexistent. Si no sabem on som, poc sabrem què cal fer per avançar.

Per exemple, mirem primer la renda disponible per als ciutadans. Si ens limitem a considerar la renta neta per càpita ens trobarem que al 2024 és inferior a la de 2009 ajustant per la inflació. És a dir que quinze anys després (!), la disponibilitat d'ingressos reals dels ciutadans no només no ha augmentat sinó que ha disminuït un 3,8%. Any 2024: 16.546€ Any 2009: 17.216€ (ajustat per la inflació 2009-2024: 35,2%). Això no ho veureu explicat habitualment a la premsa. Les dades són dures, 15 anys d'estancament econòmic són molts anys.

I si enlloc de referir-nos a la renda, ens mirem la producció sectorial veurem alts i baixos notables. No correspon ara fer-ne una anàlisi detallada. Però em referiré a un sector. Resulta que a la presentació d'un informe sobre el sector biofarmacèutic a Catalunya he observat un optimisme patològic que caldria ajustar amb un toc de realisme profund. No seré jo qui discuteixi el volum econòmic del sector, que diuen que és de 44 mil milions de facturació i que ho barreja tot, recerca, fabricació i assistència sanitària, un embolic notable. No seré jo qui discuteixi altres afirmacions de l'informe anual com les patents generades o d'altres estadístiques inexistents.

El que a aquestes alçades si que convé dir és que el conjunt de la biotecnologia no ha sabut reflectir a l'informe quins productes innovadors ha generat, quantes mol·lècules noves han aportat valor a la societat. No sabem que n'hem tret a canvi. Tant sols hi apareix l'exemple destacat del CAR-T de l'Hospital Clínic, una tecnologia desenvolupada originalment a Pensylvania. Hi deuen haver altres exemples però no surten. I llavors cal preguntar-nos perquè no s'explica què s'ha assolit amb tantes inversions (347 milions per ser exactes el 2024) o amb les inversions dels darrers cinc anys? I amb la inversió pública?

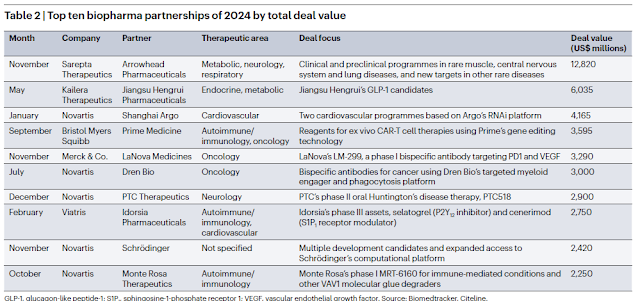

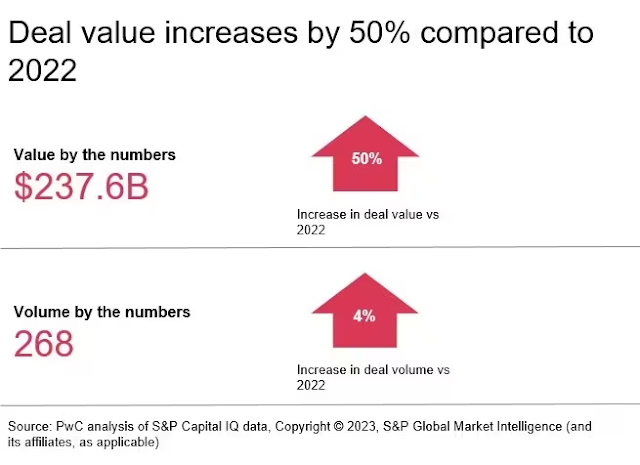

A Nature miro les fusions i adquisicions de l'any a nivell mundial, i repasso els imports. Les dades de cada operació són abismals si les volem comparar amb tot el que estem veient al nostre voltant. Són la mostra del procés de desarriscar a la innovació i de financialització del sector al que m'he referit tantes vegades i que pagarem car en els preus dels nous medicaments.

Això és el més destacat que ha passat el 2024:

Les dades parlen. No afegiré res més. Només diré que cal una dosi extra de realisme per saber on som, abans de decidir cap a on anem. Cal saber que com a sector productiu, la recerca no pot ser un objectiu en si mateix sinó que cal anar més enllà i convé traslladar-la a benestar i salut. Cal saber si tenim múscul abans de començar a caminar.