Rethinking Innovation in Drugs: A Pathway to Health for All

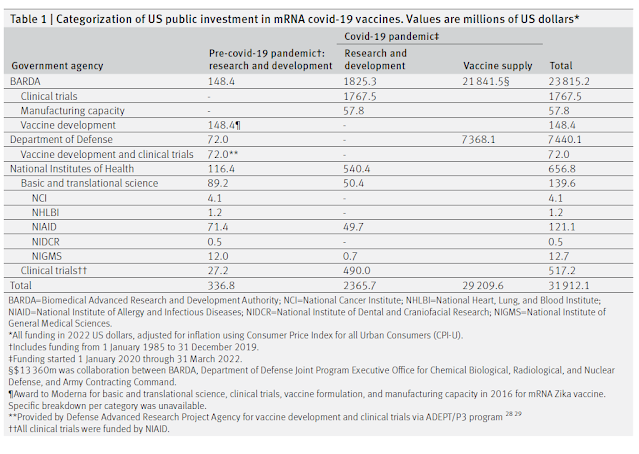

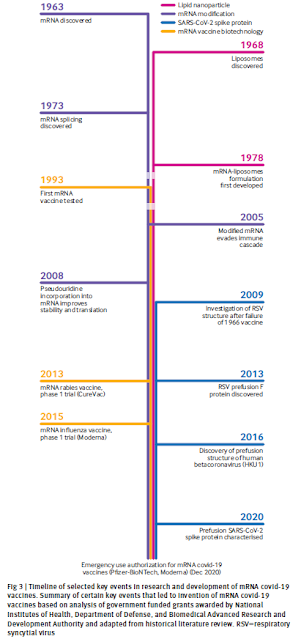

En un article recent la Mariana Mazucatto insisteix en el seu argument. És prou conegut i alhora encara convé insistir més. Cal reconèixer el paper del finançament públic a la recerca i innovació en nous medicaments. L'exemple de Moderna i la vacuna de la Covid és prou clar i ja l'he explicat anteriorment. Moderna va rebre 1000 milions $ del govern en ajudes per la recerca i alhora va comprar 1500 milions $ en vacunes per a 100 milions de dosis. El total dedicat pel govern nordamericà a la tecnologia de vacunes mRNA va ser de 31.900 milions $.

Els missatges:

- It is essential to recognize that health innovation emerges from collective intelligence

- It is imperative to bolster financial commitments to medical research and development, viewing this as a strategic long-term investment rather than a short-term expenditure, and to protect existing budgets

- It is crucial to leverage procurement mechanisms to shape market opportunities that align with public health needs

Malgrat que el finançament és imprescindible, cal una nova governança de la innovació. Unes noves prioritats de recerca i una revisió del problema de les patents. Una proposta que ja s'ha fet moltes vegades però que ningú gosa encapçalar. En altres ocasions ja ho he explicat. Malgrat que les regles del mercat són transnacionals, els governs actuen a l'àmbit nacional. S'han creat organismes multilaterals per garantir el comerç mundial però no per a la regulació necessària de la política sanitària. La OMS en aquest sentit i a l'àmbit dels medicaments afegeix poc.

While funding is essential, it alone is not the solution. Government should adopt a mission-oriented approach to drug innovation, setting bold goals related to public health that serve to catalyze innovation and investment — goals that prioritize improved patient outcomes, reduction in disease prevalence, and access equity.Achieving such bold goals would necessitate a reform of intellectual property rights. Moreover, it would require a shift in how collaborations between the public and private sectors are structured to recognize that innovation results from a collective effort, valuing contributions from both public and private entities. And it would require governments to foster collaboration across different ministries, thereby avoiding the compartmentalized governance of health. The excessive tendency of governments to outsource key operations has unfortunately weakened these capacities.