COVID-19 and Uncertainties in the Value Per Statistical Life

Do the Benefits of COVID‐19 Policies Exceed the Costs? Exploring Uncertainties in the Age–VSL Relationship

For an individual, VSL can be derived by dividing WTP by the risk reduction. A population-average VSL of $10 million indicates that the typical individual is willing to pay $1,000 to decrease the chance of dying in a given year by 1 in 10,000. Individual WTP also can be summed across individuals expected to accrue the risk reduction. If 10,000 people will experience a 1 in 10,000 risk reduction and are each willing to pay $1,000 for the risk change, the total value is $10 million (10,000 times $1,000), and one less person would be expected to die that year as calculated by 10,000 times 1/10,000.

But

Individual WTP, then, is the fundamental measure—the $1,000 in this case. The conversion to a $10 million VSL is simply for convenience.

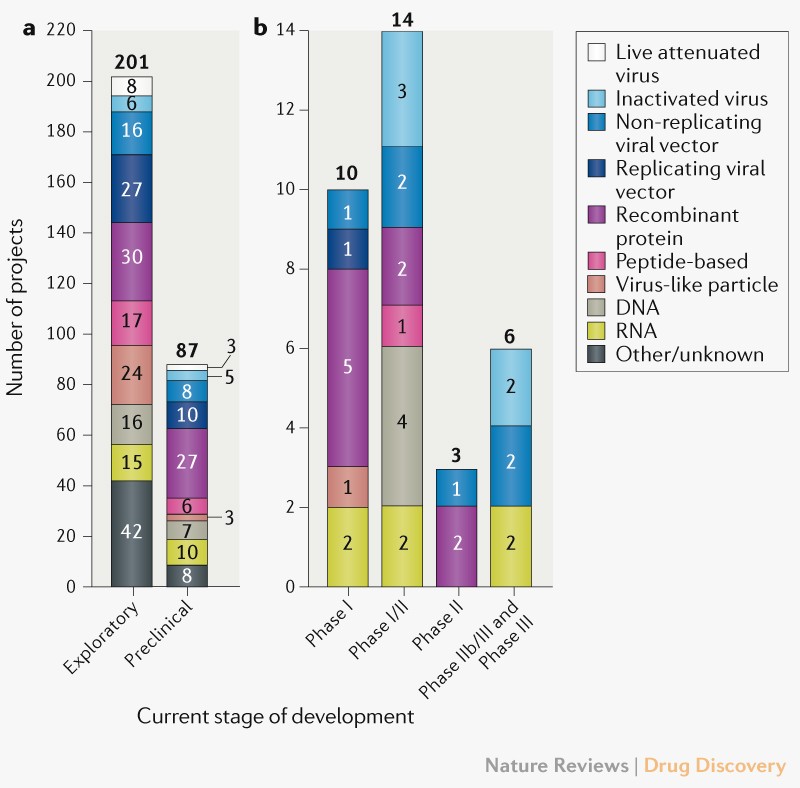

In a recent study with Ryan Sullivan and Jason F. Shogren, I compare the effects of three approaches often used to adjust for age: an invariant population-average VSL; a constant value per statistical life-year (VSLY); and a VSL that follows an inverse-U pattern, peaking in middle age. We find that when applied to the U.S. age distribution of COVID-19 deaths, these approaches result in average VSL estimates of $10.6 million, $4.5 million, and $8.5 million. The differences in these values is substantial enough to alter the conclusions of frequently cited analyses of social distancing.

Table II. VSL by Age Group (in 2019 millions of dollars)

| Age Group | Invariant VSL | Constant VSLY | Inverse‐U Relationship |

|---|

| Under 1 year | $10.63 | $13.88 | $5.38 |

| 1–4 years | $10.63 | $13.74 | $5.38 |

| 5–14 years | $10.63 | $13.37 | $5.38 |

| 15–24 years | $10.63 | $12.64 | $5.38 |

| 25–34 years | $10.63 | $11.76 | $8.50 |

| 35–44 years | $10.63 | $10.63 | $10.63 |

| 45–54 years | $10.63 | $9.19 | $10.72 |

| 55–64 years | $10.63 | $7.54 | $8.15 |

| 65–74 years | $10.63 | $5.68 | $8.15 |

| 75–84 years | $10.63 | $3.72 | $8.15 |

| 85 years and over | $10.63 | $2.03 | $8.15 |

Table III. COVID‐19 Age‐Weighted Value (in 2019 millions of dollars)

| Invariant VSL | Constant VSLY | Inverse‐U Relationship |

|---|

| Total value, all COVID‐19 deaths | $937.6 billion | $394.8 billion | $773.4 billion |

| Average VSL, weighted by COVID‐19 deaths by age | $10.63 million | $4.47 million | $8.31 million |

Table IV. Effect of Alternative Approaches on Analytic Results | | ————————————————‐Benefits————————————‐———— |

|---|

| | Lives | Original | Invariant | Constant | Inverse‐U |

|---|

| | Costs | Saved | Approach | VSL | VSLY | Relationship |

|---|

| Thunström et al. (2020) | $7.2 trillion | 1.24 million | $12.4 trillion | $13.16 trillion | $5.54 trillion | $10.30 trillion |

| Greenstone and Nigam (2020) | N/A | 1.76 million | $7.94 trillion | $18.72 trillion | $7.88 trillion | $14.64 trillion |

| Acemoglu et al. (2020) | $2.15 trillion | 8.7 million | N/A | $92.44 trillion | $38.93 trillion | $72.31 trillion |

Does this make sense? It seems quite high. If we value identified life more than a statistical life, can you imagine the final figure?

Whether the social distancing policy considered by Thunström et al. (2020) yields net benefits varies depending on the valuation approach. The authors use an invariant VSL but apply a somewhat lower value than we use in our analysis ($10 million rather than $10.63 million). However, both our invariant VSL and inverse‐U approaches lead to positive net benefits. Under our invariant approach, the benefits increase by almost $800 billion due to differences between the VSL estimates. Benefits decrease when using the inverse‐U approach, but not by a large enough amount to drop below estimated costs. Under the constant VSLY approach, benefits decrease by a substantial amount and the policy no longer appears cost‐beneficial.

While Greenstone and Nigam (2020) do not include a cost estimate in their calculations, the effects of our three approaches on their featured benefit estimates are significant. The benefit estimates more than double when applying the invariant VSL approach rather than their age‐adjusted approach. Interestingly, their estimates are very similar ($7.94 vs. $7.88 trillion) to the results using our constant VSLY method, while applying our inverse‐U estimates almost doubles the value in comparison to their inverse‐U approach. This result reflects the relative steepness of their curve at older ages as well as our assumption that values level off at older ages under the inverse‐U approach. As noted earlier, the additional sensitivity analyses reported by the authors also show siginificant variation in the results.

Acemoglu et al. (2020) have by far the largest estimates of lives saved across the three social distancing studies, which naturally increases the benefit values. Under all three approaches, we find that benefits exceed costs by an order of magnitude. However, Acemoglu et al. (2020) find that approaches other than the scenario reflected in Table IV are more cost‐effective, particularly if they target higher risk, older age groups.

Anyway, let's search a little bit more on that. Let's take the press. I don't think that this helps to take policy decisions in the current pandemic. It's just recreational research.

PS. The price of freedom is 103€ per day in my country (cost of non being free by mistake). Explained here.

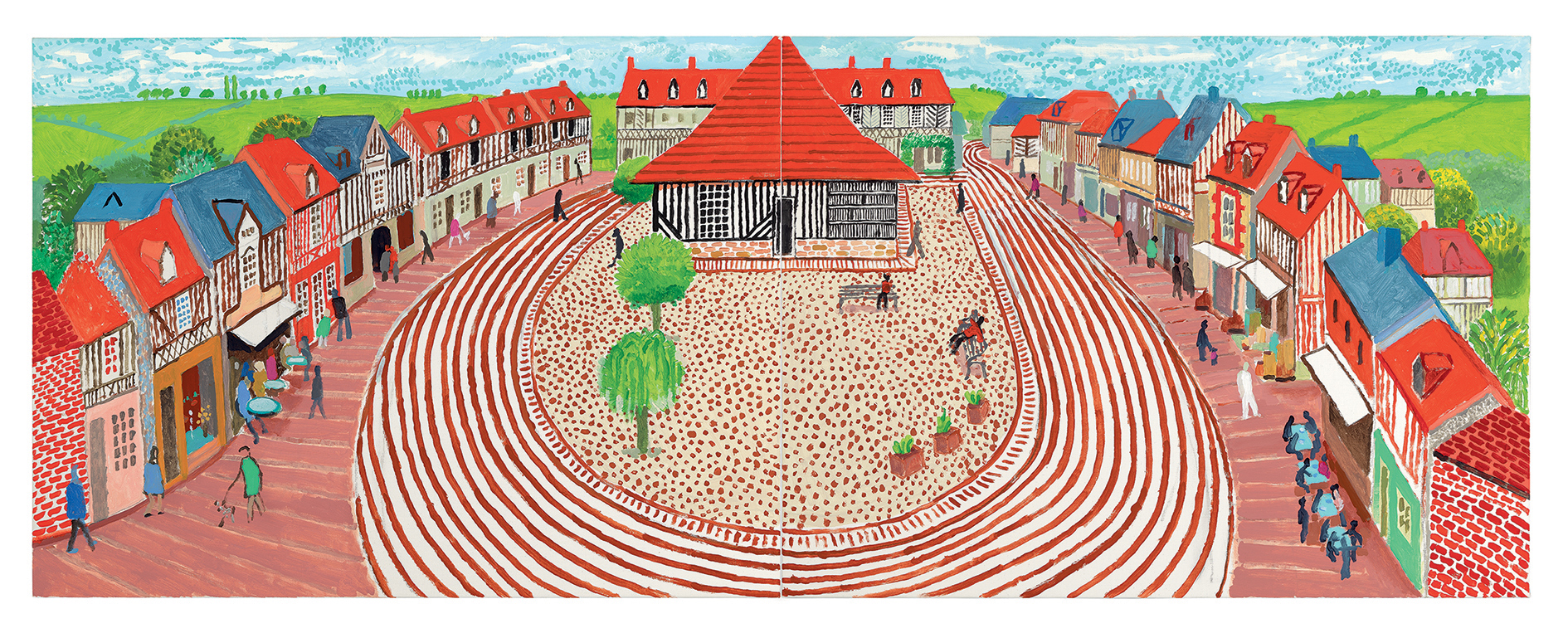

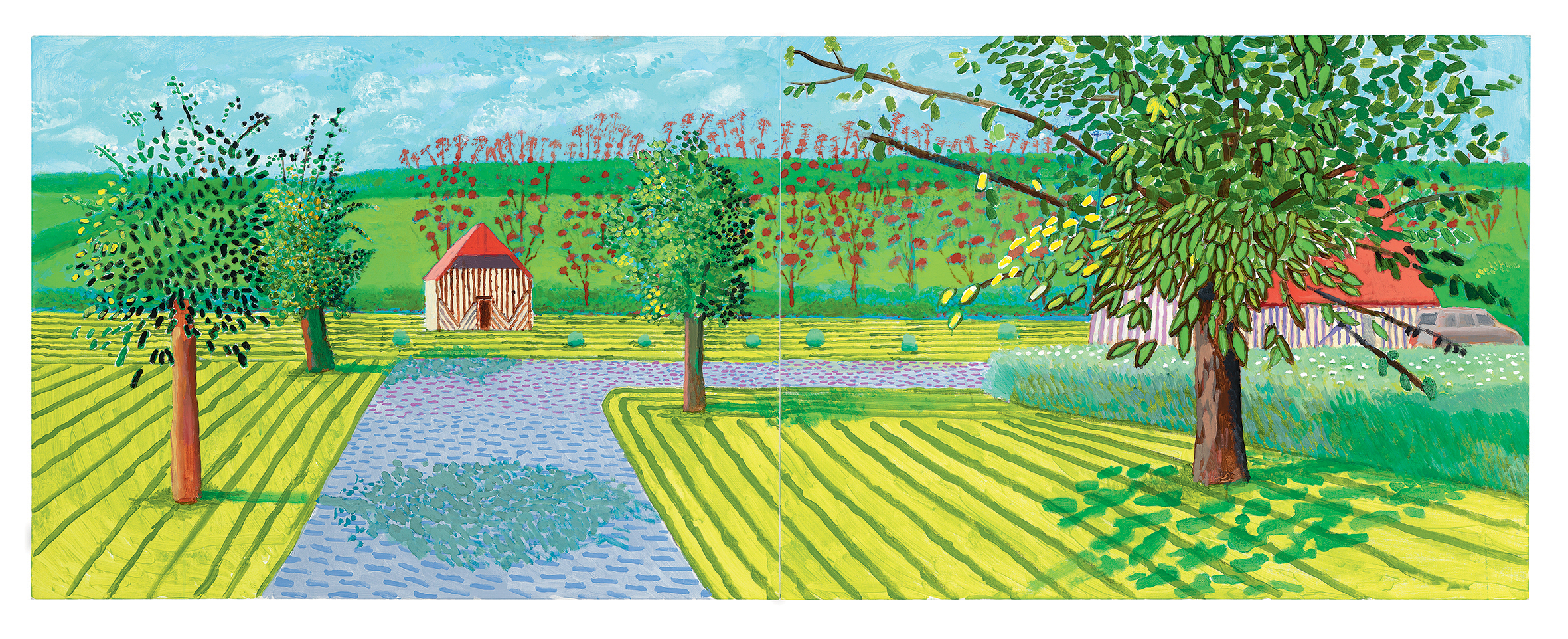

Hockney