The Price of Panic. How the Tyranny of Experts Turned a Pandemic into a Catastrophe

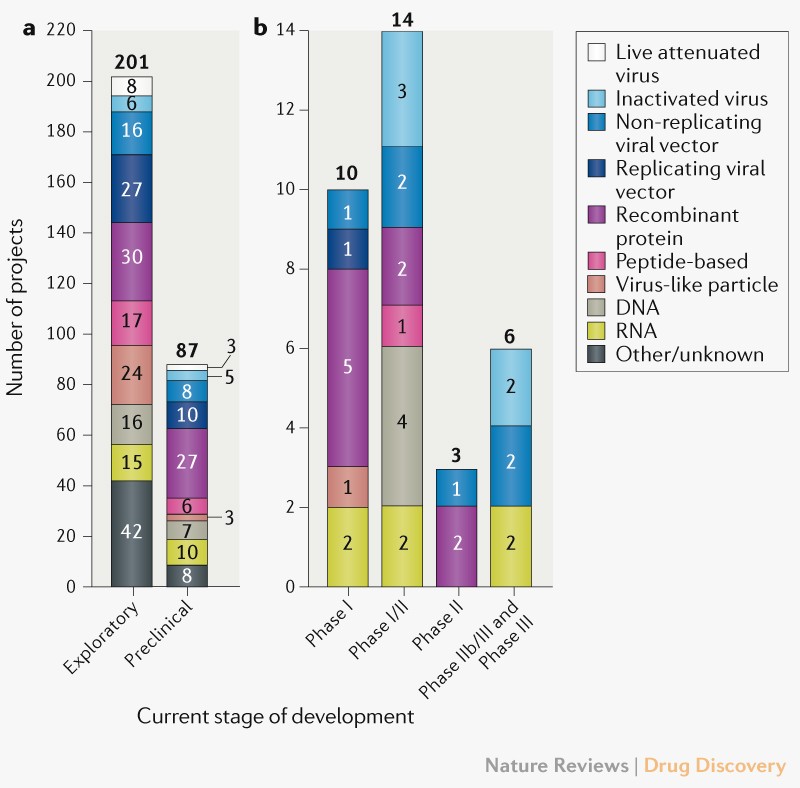

So, what caused the viral panic? The panic and lurching government overreach were inspired not so much by deaths people knew about firsthand, and not so much by the virus’s murky origins in China. They were sparked by a few forecasts that had the smell of science. The World Health Organization (WHO) favored a single, untested, apocalyptic model from Imperial College London. The United States government took its cues from the Institute for Health Metrics & Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington. We now know these models were so wrong they were like shots in the dark. After a few months, even the press admitted as much. But by then vast damage had been done.

But what of those experts? They treated predictive models—which are at best complex conjectures about future events—as if they were data. And then, when the models flopped, they began to massage the data. To get past this catastrophe we will need to forgive, but we should never forget. We should do whatever we can to dismantle such experts’ unchecked power over public policy.

These experts, however, could never have done so much damage without a gullible, self-righteous, and weaponized media that spread their projections far and wide. The press carpet-bombed the world with stories about impending shortages of hospital beds, ventilators, and emergency room capacity. They served up apocalyptic clickbait by the hour and the ton.

History shows that you will rarely lose your job making predictions if you’re wrong in the right direction. On the other hand, you may well lose it if you’re right in the wrong direction. Neither rulers nor subjects welcome the bearer of bad, but true, news. (Especially if it’s bad news for power-grabbing elites.)

Being wrong in the right direction, though, often reaps reward. Early pandemic models indicated that only prompt and massive state action could save us. The models were wrong—way off—but they were wrong in the right direction. They gave politicians justification for taking over almost every aspect of citizens’ lives. They gave the press clickbait galore. We’re not assuming malice here. We assume that many of these folks were moved by concern and even love for others. The issue is one of incentives and human nature, not bad intentions.

Our imagined pandemic model has made a huge mistake. How to explain that whopping error? In a perfect world, the experts who created the model, publicized, and used it to create public policy would reassess the assumptions they fed into the model—A, B, and C—find the mistake, and try new ones, which may better match the “observables.”

But we don’t live in a perfect world with perfect experts. What if experts are loath to admit that they were wrong? (We know that’s a real stretch, but stick with us here.) What if they have been feted by the press and promoted to positions of authority and power? They have other options besides the humiliating one of going back to the drawing board. For starters, such experts can stop using the word “predictions” to describe the forecasts that the model has been spitting out. Now they’re just “scenarios” or “guidelines” or “projections.” But these are just word games. There’s little daylight between a forecast, a prediction, a guess, a scenario, and a projection. All those words describe what the model is doing when it says, If A, B, and C are true, then something like X will happen, give or take a margin of error. If nothing like X happens, then something’s wrong with at least one of the model’s conceptual inputs, that is, with one of the propositions that that model assumed to be true. At least one of A, B, or C must be wrong.

It's only one view. Uncertainty is everywhere, and you may find snake-oil sellers in every corner.

PS. Tomorrow online presentation.

PS. Great post on pandemic models.