The delays in coronavirus testing can be explained by shortage of stocks from the supply side, mismatchs between supply and demand and from incomplete information about the current offer of tests in the market. Somebody should analyse this in detail and give some explanations. Why there is no international body to coordinate such decisions?. Can the market provide an equilibrium and give the right answer to the pandemic testing?.

It is quite surprising that there are so many companies providing such tests. Have a look at this site FINDDX, you'll see many options, from molecular diagnostics to inmunoassays. Unless somebody can assess current production capacity and available stock, current shortages may be a false signal of mismatch.

Up to now everybody has been talking about PCR test, but you may get right now antibody detection IgG IgM and this could add valuable information. Inmunoassay tests would help to understand those who are already inmunized, though with less precision. If so, we could reduce current social distancing prescriptions after a window period. If those that show positive IgG can avoid lockdown, then this could help a lot.

PS. If you want to know how many tests have been performed up to now, check this website.

PS. Just one minor issue. Spain says that has made 30.000 tests. Right now we already have 33.089 confirmed cases !. Data and statistics from Spain are a complete disaster. It is not possible a positive result in more than 100% tests!

23 de març 2020

22 de març 2020

On rationing (ventilators)

Recomendaciones éticas para tomar decisiones en la situación excepcional de crisis por pandemia Covid-19 en las UCI

These are tough times for mankind. We are social animals and current instructions/recommendations are focused to behave exactly the opposite. Once the coronavirus hits someone, the result may be being hospitalised and one may need intensive care and mechanical ventilation. And if supply is not enough for the demand of ventilators, then starts the most difficult question: who gets the ventilator?. A professional answer is needed. Fortunately the scientific society Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias has released a document that helps to provide specific recommendations in such situation.

This is exactly what we can expect from a modern society. Professional decisions need guidance and consensus. There is no role for politicians in this issue and in this moment, scientific societies have to coordinate such efforts. Therefore my congratulations for their recommendations.

Basically, the document highlights the criteria of maximizing capability of benefit, and in the current situation and in intensive care, this has to be applied in a general way, for covid-19 and non covid-19 disease requiring such services. And these criteria should be applied in an uniform way.

In this blog I've been supporting the role of professionalism in taking tough decisions. Today I've to say that these is a good example of rationing to keep in mind.

PS. If projects like this one succeed, then tough decisions could be avoided. Great initiative.

These are tough times for mankind. We are social animals and current instructions/recommendations are focused to behave exactly the opposite. Once the coronavirus hits someone, the result may be being hospitalised and one may need intensive care and mechanical ventilation. And if supply is not enough for the demand of ventilators, then starts the most difficult question: who gets the ventilator?. A professional answer is needed. Fortunately the scientific society Sociedad Española de Medicina Intensiva, Crítica y Unidades Coronarias has released a document that helps to provide specific recommendations in such situation.

This is exactly what we can expect from a modern society. Professional decisions need guidance and consensus. There is no role for politicians in this issue and in this moment, scientific societies have to coordinate such efforts. Therefore my congratulations for their recommendations.

Basically, the document highlights the criteria of maximizing capability of benefit, and in the current situation and in intensive care, this has to be applied in a general way, for covid-19 and non covid-19 disease requiring such services. And these criteria should be applied in an uniform way.

In this blog I've been supporting the role of professionalism in taking tough decisions. Today I've to say that these is a good example of rationing to keep in mind.

PS. If projects like this one succeed, then tough decisions could be avoided. Great initiative.

21 de març 2020

Social distancing in times of pandemics

These are the values in normal conditions:

Huge differences across countries!

Nowadays, during pandemics, social distancing means confinement.

20 de març 2020

Economics of pandemics

There is a new free ebook available on the economics of current pandemics that was finished on March 5h. These are the contents:

Introduction: Richard Baldwin and Beatrice Weder di Mauro

1 Macroeconomics of the fluFrom Joachim Voth chapter:

Beatrice Weder di Mauro

2 Tackling the fallout from COVID-19

Laurence Boone

3 The economic impact of COVID-19

Warwick McKibbin and Roshen Fernando

4 Novel coronavirus hurts the Middle East and North Africa through many channels

Rabah Arezki and Ha Nguyen

5 Thinking ahead about the trade impact of COVID-19

Richard Baldwin and Eiichi Tomiura

6 Finance in the times of coronavirus

Thorsten Beck

7 Contagion: Bank runs and COVID-19

Stephen G. Cecchetti and Kermit L. Schoenholtz

8 Real and financial lenses to assess the economic consequences of COVID-19

Catherine L. Mann

9 As coronavirus spreads, can the EU afford to close its borders?

Raffaella Meninno and Guntram Wolff

10 Trade and travel in the time of epidemics

Joachim Voth

11 On plague in a time of Ebola

Cormac O Grada

12 Coronavirus monetary policy

John H. Cochrane

13 The economic effects of a pandemic

Simon Wren-Lewis

14 The good thing about coronavirus

Charles Wyplosz

First, is a massive restriction of mobility desirable? And second, is it feasible at all? An economically rational answer to the first question should begin with the value of a human life. With all the reservations that one can have against such calculations from a philosophical point of view, cost-benefit considerations without numbers for the value of a human life are not feasible. However, estimates regularly show an enormous range; the average is around US$10 million per person (Viscusi and Masterman 2017). This means that even before the epidemic has peaked, COVID-19 caused an immediate cost of $26 billion in deaths. If the epidemic ends with a maximum of 10,000 deaths (four times the current value), the value of life destroyed would be approximately $100 billion.Up to now,this is the only chapter I've read from these promising book.

The costs must be compared with the enormous gains in economic performance that the free exchange of goods and people has made possible. In China alone, hundreds of millions of people have escaped deepest poverty during the past 20 years. In 1980, more than half of the Chinese population lived on less than $2 a day; in 1998, it was less than a quarter (Sala-i-Martin 2006). Around the world, people have escaped the poverty trap wherever the free movement of goods and people has become possible. And richer regions also benefit massively, often in surprising ways.

19 de març 2020

To test or not to test (for coronavirus) (2)

Some days ago I was explaining the rationale for coronavirus testing regarding clinical decision making. However, as we all know, individual behavior is also capable to produce health and disease contagion. Therefore, in case of coronavirus, behavioral externalities are crucial and nowadays we have denominated them "social distancing".

Having said that, there is an additional behavioral value from testing to take into account. If all individuals in a population have access to the test, maybe everybody is aware of social distancing than in a situation than only suspected cases receive the test. Behaviors may change, and quarantine strategies more successful. In such situation it is much more feasible to restrict mobility. Let's take for example what this article explains:This paper studies the effect of public policies to restrict migration by individuals suspected of carrying disease, when those individuals do not know for certain whether they have the disease but may have more information than the authorities about their probability of being carriers. It has long been known that migration affects the spread of

disease, and this influence has for centuries been used to justify placing restrictions on the movement of individuals suspected of carrying infections.

Epidemiological studies have addressed how individual behaviour, among other factors, affects the spread of infections. However, the study of how individual behaviour in turn

changes in response to the new incentives created by the occurrence of a disease is much less developed. The principal contribution of our paper is to bring the study of strategic behavior under uncertainty into the domain of epidemiology, and to analyze its impact, in interaction with public policies, on the overall impact of epidemic disease.

Migration as a form of preventive behaviour has received very little attention, although evidence has accumulated that migration behaviour and epidemics are intrinsically linked. Migration behaviour can respond very rapidly to changes in the health environment, in particular when it suddenly deteriorates through epidemics.

In our model we show that:

• First, when the disease is concentrated in one place (the epicentre of an epidemic for instance), a decision to migrate away from the epicentre brings a potentially infected individual in contact with more uninfected individuals than she would have met had she

remained where she was. Thus the typical migrant imposes a net negative externality as a result of her decision to migrate, and the marginal migrant (for whom, by definition, private benefits of migrating just equal the private costs of doing so) has a negative

impact on social welfare. Laissez faire will therefore lead to excessive migration. This provides a rationale for the frequent (and frequently justified) public policy response to epidemics, which is to attempt to restrict migration away from the epicentre by those who may be infected.

• Secondly, and less obviously, not all policies that aim to restrict migration in fact do so. In particular, we distinguish two effects of quarantine policies. The first is that they raise migration costs, which lowers migration. For example, mandatory health certificates or test results may be required by health authorities to leave the epicentre of the disease.We call this a “type 1” effect of quarantine measures. The second effect is that they impose a utility cost on individuals of remaining in the city where quarantine measures are effective, since they face a chance of being subjected to awkward and possibly

dangerous restrictions on their movements. We call this a “type 2” effect of quarantine measures. Such measures impose a welfare cost on those who suffer them, which tends to increase migration by those who are not currently subject to quarantine but fear they may become so if they remain where they are. Policies implemented without taking type 2 effects into account may therefore have results that are opposite from those intended.

• Thirdly, even policies that actually reduce migration may have an adverse impact on social welfare if they reduce migration “too much”, and specifically if they discourage those intra-marginal migrants whose private benefits from migration substantially

exceed their private costs of migration, by enough to outweigh the negative externality they impose on others. Overall disease prevalence may even increase if in the name of avoiding negative externalities the authorities discourage relatively low-risk individuals

from escaping the epicentre of the disease, thereby increasing the probability that they will catch the disease there from infected individuals.

When people have imperfect information about their own infection status, migration imposes net negative externalities by increasing the rate of exposure faced by the uninfected outside the epicentre of the epidemic. In and of itself, this our paper has highlighted the fact that although quarantine of individuals who have been identified as sick reduces (obviously) the propensity of these individuals to migrate and spread the disease, the threat of quarantine increases the propensity to migrate of other individuals who have not yet been fallen sick but who know themselves to be at risk.Quarantine measures have all these effects. However, if information about contagion is confirmed, then behaviors may change, and mandatory health certificates can be issued. The case of the italian village of Vò confirms that population screening has been successful in stopping the outbreak. This could have been done at the beginning if diagnostics kits had been available. Right now it seems an unfeasible strategy. We know now that there is a behavioral value of test information, beyond the clinical value. And in the case of coronavirus, confirmatory tests provide only partial information. In case of non infection, incubation period is uncertain, and some days after can be confirmed. Therefore, quarantine measures have to be mandatory and strict for the whole population and for specific areas.

18 de març 2020

Current coronavirus pandemic in context

The Pandemic Century. One Hundred Years of Panic, Hysteria and Hubris

Some months ago in the best books of FT 2019, I listed this one. and the summary is:

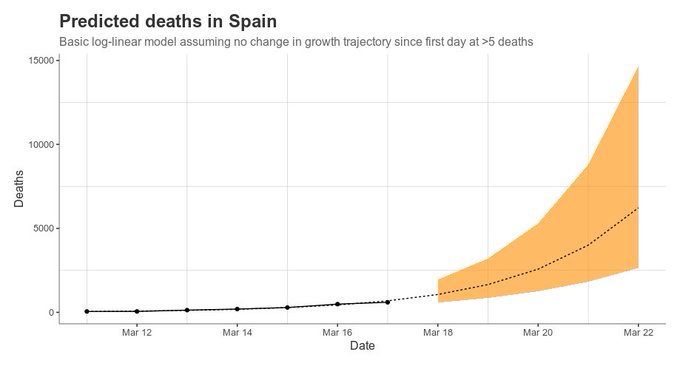

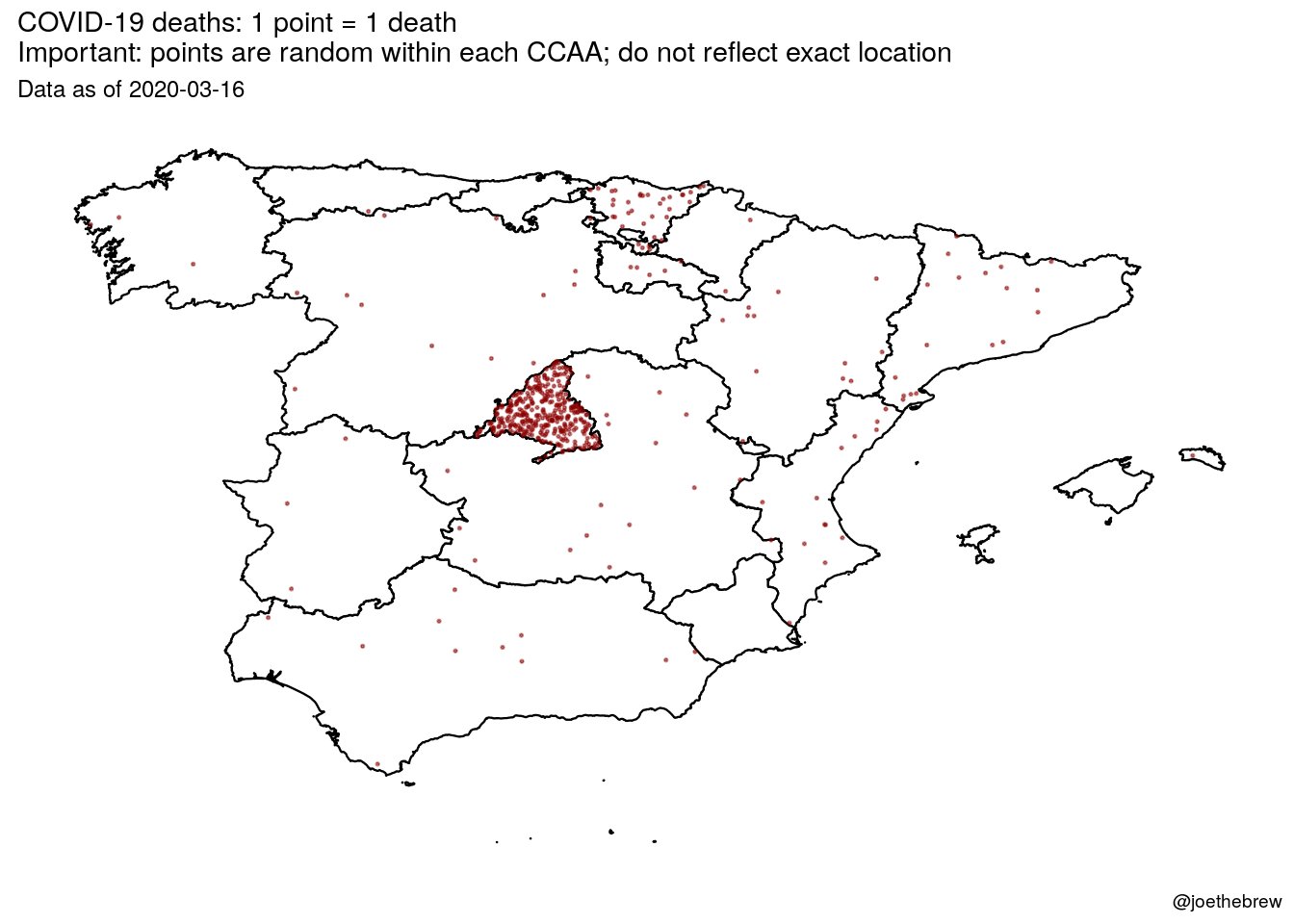

Just have a look at what's going on in Madrid. This is horrendous! And politicians don't want to close Madrid! And they have allowed to spread contagion outside. Somebody should say it louder. International health rules should prevail over spanish rulers.

Beyond politicians, there are experts.

Some months ago in the best books of FT 2019, I listed this one. and the summary is:

The Pandemic Century exposes the limits of science against nature, and how these crises are shaped by humans as much as microbes.This is exactly what is happening right now!!! Contagion is shaped also by politicians.

Just have a look at what's going on in Madrid. This is horrendous! And politicians don't want to close Madrid! And they have allowed to spread contagion outside. Somebody should say it louder. International health rules should prevail over spanish rulers.

Beyond politicians, there are experts.

Battered by their repeated failure to predict deadly outbreaks of infectious disease, even the experts have come to recognize the limits of medical prognostication. This is not only because microbes are highly mutable—that has been known since Pasteur’s time—but because we are continually lending them a helping a hand. Time and again, we assist microbes to occupy new ecological niches and spread to new places in ways that usually only become apparent after the event. And to judge by the recent run of pandemics and epidemics the process seems to be speeding up.

Reviewing the last hundred years of epidemic outbreaks, the only thing that is certain is that there will be new plagues and new pandemics. It is not a question of if, we are told, but when. Pestilences may be unpredictable but we should expect them to recur. However, what Camus could not have foreseen is that the attempt to anticipate disaster also creates new distortions and introduces new uncertainties. Twice this pandemic century, in 1976 and again in 2003, scientists thought the world was on the brink of a new influenza pandemic, only to realize that the outbreaks were false alarms and that the real danger lay elsewhere. Then in 2009 the WHO declared that the Mexican swine flu, a ressortment of two well-known H1N1 swine-lineage viruses that had circulated separately for over a decade, met the criterion of a pandemic virus, triggering the activation of global pandemic preparedness plans. On paper, this was the first pandemic of the twenty-first century and the first influenza pandemic in forty-one years. The fact that the swine flu was an H1N1, just like the Spanish flu, raised the prospect that this might be the Big One and that governments should expect a wave of illness and deaths similar to that in 1918–1919. But though the WHO’s declaration sparked widespread panic, the anticipated viral Armageddon never materialized. Instead, when it was realized that the Mexican swine flu was no more severe than a seasonal strain of flu, the WHO was accused of “faking” the pandemic for the benefit of vaccine manufacturers and other special interests. The result is what Susan Sontag calls “a permanent modern scenario: apocalypse looms . . . and it doesn’t occur.” As we look to the next one hundred years of infectious disease outbreaks, let us hope that is one prognostication that turns out to be true.

17 de març 2020

Modeling coronavirus pandemic

Charting the Next Pandemic

Modeling Infectious Disease Spreading in the Data Science Age

This book was published last year and is a reference for pandemic modeling and in one chapter says:

• R0 = 2.7

• Starting date: varies by geographical location

SCENARIOS

Reduction of transmissibility:

• 30% after 4 weeks; 50% after 7 weeks

• 50% after 4 weeks, 90% after 7 weeks

Origin:

Barcelona, Spain

15 million

passengers/year

Guangzhou, China

Jeddah,

Saudi Arabia

21 million

passengers/year

You may find a recent example of its application in this Science article.

There is only one minor thing that the model can't consider. It is the politicans' and citizens decisions:

Different strategies in a globalized world are the seed of caos beyond the pandemic. Nowadays, this is the current situation. However, as this blogs explains:

Modeling Infectious Disease Spreading in the Data Science Age

This book was published last year and is a reference for pandemic modeling and in one chapter says:

In the case of coronaviruses, we selected scenarios referring to a case with a transmission rate and natural history of the disease similar to the SARS virus. Thus we assume that the infectiousness of individuals starts only after the onset of clinical symptoms, and we consider the absence of asymptomatic infections. Although we take into account a relatively high reproduction number R0=2.7, the absence of asymptomatic transmission makes all containment measures based on the timely isolation of cases viable and very effective. We therefore consider, for each possible initial condition of the outbreak, two scenarios with a transmissibility reduction, due to prompt case isolation, of 30% and 50% after the first 4 weeks and 50% and 90% after the seventh week, respectively.STARTING CONDITIONS

Contrary to influenza, we do not consider seasonal variations because seasonal forcing does not appear to have a large impact on SARS. For this reason, we consider only one starting date during the calendar year for each geographical location. In total we provide six scenarios summarized in the infographic charts. The typical coronavirus chart layout and the “how to read it” guide can be found on the following pages.

• R0 = 2.7

• Starting date: varies by geographical location

SCENARIOS

Reduction of transmissibility:

• 30% after 4 weeks; 50% after 7 weeks

• 50% after 4 weeks, 90% after 7 weeks

Origin:

Barcelona, Spain

15 million

passengers/year

Guangzhou, China

Jeddah,

Saudi Arabia

21 million

passengers/year

You may find a recent example of its application in this Science article.

There is only one minor thing that the model can't consider. It is the politicans' and citizens decisions:

Different strategies in a globalized world are the seed of caos beyond the pandemic. Nowadays, this is the current situation. However, as this blogs explains:

There is not a single “one-size-fits-all” approach that allows to respond effectively to the ongoing and rapidly evolving situation. Each country needs to tailor its response in accordance with the capacities of its health systems, its economic resources and infrastructure, and the degree of collective and individual responsibility and compliance with recommendations issued by the authorities. The next generation of health professionals will look back at the different responses to COVID-19 described above and hopefully draw lessons for future infectious disease epidemics.Meanwhile modeling provides little help.

Subscriure's a:

Missatges (Atom)