Alvin Roth in

his book sheds light on the field known as Market design. Given a set of agents, market design seeks to identify the game rules that might be implemented and that would produce the desired behaviors in the players. In some markets, prices may be used to induce the desired outcomes—these markets are the study of auction theory. In other markets, prices may not be used—these markets are the study of matching theory.

Until recently, economists often passed quickly over matching and focused primarily on commodity markets, in which prices alone determine who gets what. In a commodity market, you decide what you want, and if you can afford it, you get it.The price does all the work, bringing the two of you together at the price at which supply equals demand.

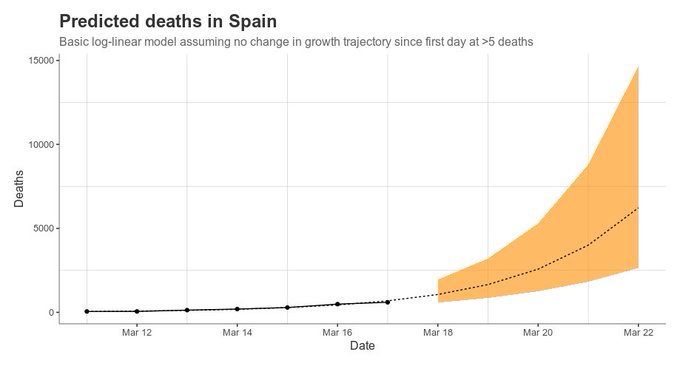

The first question is, can we consider lab tests for a pandemic a commodity?. My impression is that once a virus pandemic has appeared, we need the sequencing for the genome of the virus and after that, several suppliers may offer different options with a high level of uncertainty. Buyers are blind about the options for testing. Suppliers don't know about the extent of the outbreak and the need of tests. The market is rising. In such situations the criteria should be to allocate most of the production to the place where the outbreak has started, in order to prevent contagion. Price may distort this allocation because other countries and buyers may strategically move first to achieve strategic reserves.

Alvin Roth says:

The first task of a successful marketplace is bringing together many participants who want to transact, so they can seek out the best transactions. Having a lot of participants makes a market thick.

Congestion is a problem that marketplaces can face once they’ve achieved thickness. It’s the economic equivalent of a traffic jam, a curse of success. The range of options in a thick market can be overwhelming, and it may take time to evaluate a potential deal, or to consummate it. Marketplaces can help organize potential transactions so that they can be evaluated fast enough that if particular deals fall through, other opportunities will still be available. In commodity markets, price does this well, since a single offer can be made to the entire market (“Anyone can buy a pint of my raspberries for $5.50”), but in matching markets, each transaction may have to be considered separately.

Decisions that depend on what others are doing are called strategic decisions and are the concern of the branch of economics called game theory. Strategic decision making plays a big role in determining who does well or badly in many selection processes. Often when we game theorists study a matching process, we learn how participants “game the system.” Well-designed matching processes try to take into account the fact that participants are making strategic decisions.

When a market doesn’t deal effectively with congestion and participants may not be able to find the transactions they want, it might not be safe for them to wait for the marketplace to open if some opportunities are available earlier. Even when going early isn’t an option, the marketplace might force participants to engage in risky gambles.

The range of tests may be overwhelming, as it is right now with coronavirus. How can we manage such congestion?

There is a chapter in the H

andbook of Market Design by Paul Klemperer about The Product-Mix Auction: A New Auction Design for Differentiated Goods. I've read what he proposes and I think that fits quite well with the market for lab tests in a pandemic. Of course, additional details are needed. The research question is:

How should goods that both seller(s) and buyers view as imperfect substitutes be sold, especially when multi-round auctions are impractical?

My design is straightforward in concept—each bidder can make one or more bids, and each bid contains a set of mutually exclusive offers. Each offer specifies a price (or, in the Bank of England's auction, an interest rate) for a quantity of a specific "variety." The auctioneer looks at all the bids and then selects a price for each "variety." From each bid offered by each bidder, the auctioneer accepts (only) the offer that gives the bidder the greatest surplus at the selected prices, or no offer if all the offers would give the bidder negative surplus. All accepted offers for a variety pay the same (uniform) price for that variety.

The idea is that the menu of mutually exclusive sets of offers allows each bidder to approximate a demand function, so bidders can, in effect, decide how much of each variety to buy after seeing the prices chosen. Meanwhile, the auctioneer can look at demand before choosing the prices; allowing it to choose the prices ex post creates no problem here, because it allocates each bidder precisely what that bidder would have chosen for itself given those prices. Importantly, offers for each variety provide a competitive discipline on the offers for the other varieties, because they are all being auctioned simultaneously.

Compare this with the "standard" approach of running a separate auction for each different "variety." In this case, outcomes are erratic and inefficient, because the auctioneer has to choose how much of each variety to offer before learning bidders' preferences, and bidders have to guess how much to bid for in each auction without knowing what the price differences between varieties will turn out to be; the wrong bidders may win, and those who do win may be inefficiently allocated across varieties. Furthermore, each individual auction is much more sensitive to market power, to manipulation, and to informational asymmetries than if all offers compete directly with each other in a single auction. The auctioneer's revenues are correspondingly generally lower. All these problems also reduce the auctions' value as a source of information. They may also reduce participation, which can create "second-round" feedback effects further magnifying the problems.

The rules of the auction are as follows:

1. Each bidder can make any number of bids. Each bid specifies a single quantity and an offer of a per-unit price for each variety. The offers in each bid are mutually exclusive.

2. The auctioneer looks at all the bids and chooses a minimum "cut-off" price for each variety

3. The auctioneer accepts all offers that exceed the minimum price for the corresponding variety, except that it accepts at most one offer from each bid. If both price offers in any bid exceed the minimum price for the corresponding variety, the auctioneer accepts the offer that maximizes the bidder s surplus, as measured by the offer's distance above the minimum price.

4. All accepted offers pay the minimum price for the corresponding variety—that is, there is "uniform pricing" for each variety

It is easy to include additional potential sellers (i.e., additional lenders of funds, in our example). Simply add their maximum supply to the total that the auctioneer sells, but allow them to participate in the auction as usual. If a potential seller wins nothing in the auction, the auctioneer has sold the sellers supply for it. If a potential seller wins its total supply back, there is no change in its position

My impression is that lab tests in a pandemic require a market design, current allocation methods are relying in a

free market that doesn't allows to create value where it it most needed.

Just a final words by

Alvin Roth:

Because economics touches on just about everything, economists have an opportunity to learn something from just about everyone, and I’ve met and worked with some remarkable people in each of the markets I’ve helped design.

Market design is giving new scope to the ancient profession of matchmaking. Consider this book a tour of the matching and market making happening around us. I hope it will give you a new way to see the world and to understand who gets what—and why.