Jenifer Doudna publishes a must read review article on genome editing in Nature this week.

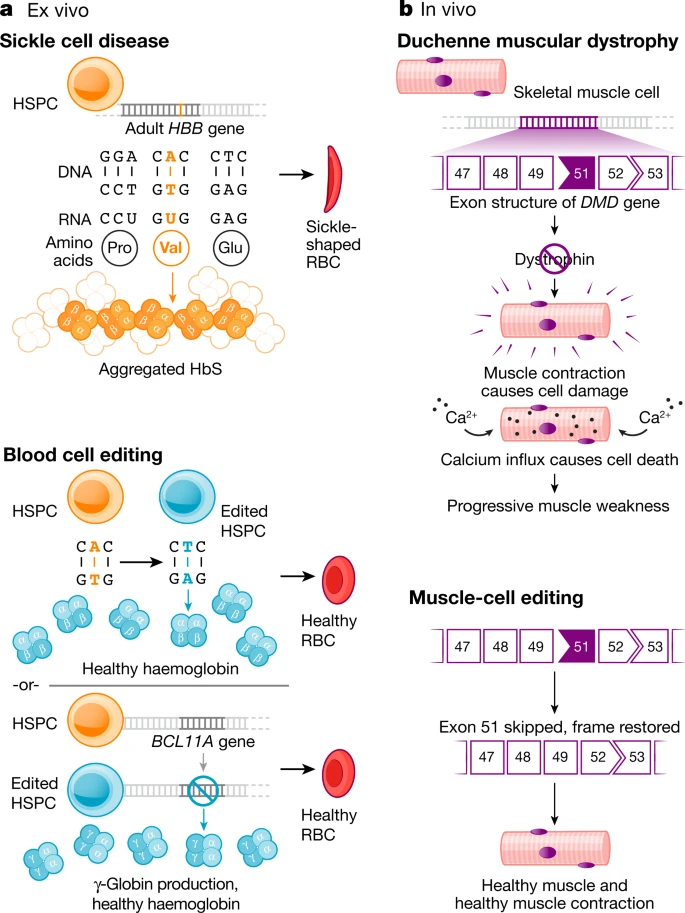

Current clinical trials using the CRISPR platform aim to improve chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell effectiveness, treat sickle cell disease and other inherited blood disorders, and stop or reverse eye disease. In addition, clinical trials to use genome editing for degenerative diseases including for patients with muscular dystrophy are on the horizon.

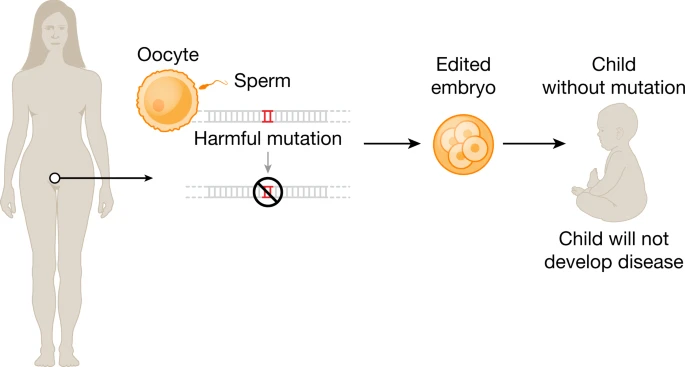

Notably, all of the genome-editing therapeutics under development aim to treat patients through somatic cell modification. These treatments are designed to affect only the individual who receives the treatment, reflecting the traditional approach to disease mitigation. However, genome editing offers the potential to correct disease causing mutations in the germline, which would introduce genetic changes that would be passed on to future generations.

At the time of writing, international commissions convened by the World Health Organization (WHO) and by the US National Academy of Sciences and National Academy of Medicine, together with the Royal Society, are drafting detailed requirements for any potential future clinical use.Meanwhile, CRISPR is closer than you think.

Fig. 1: Ex vivo and in vivo genome editing to treat human disease.

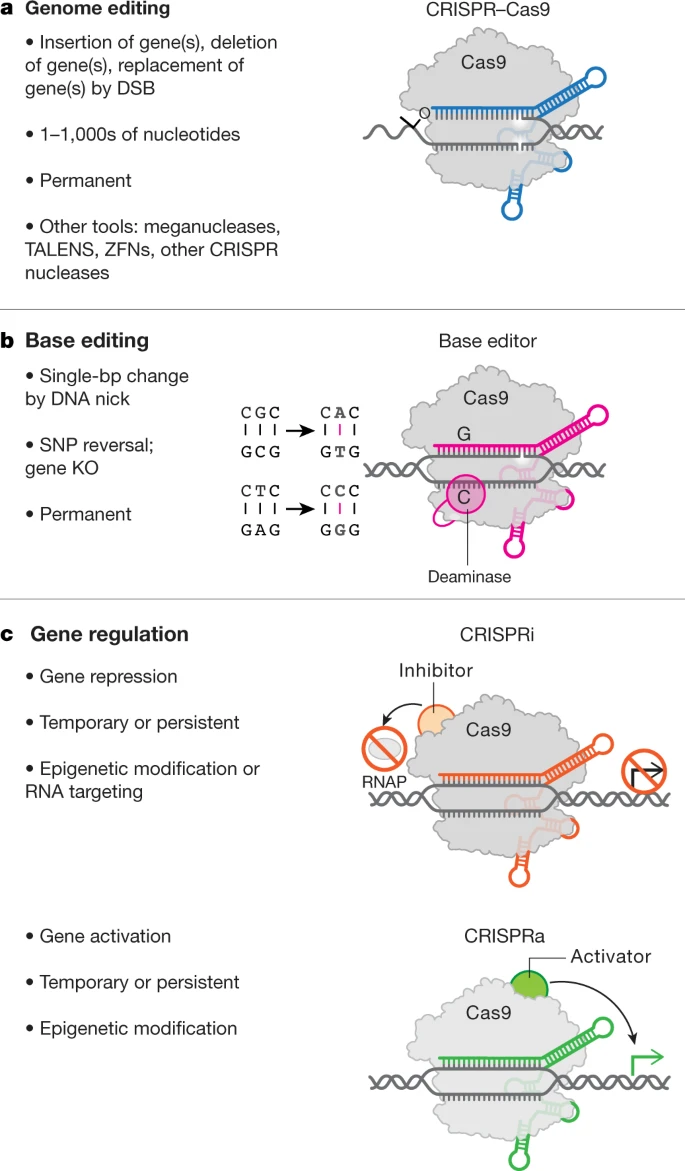

Fig. 2: The genome editing toolbox.

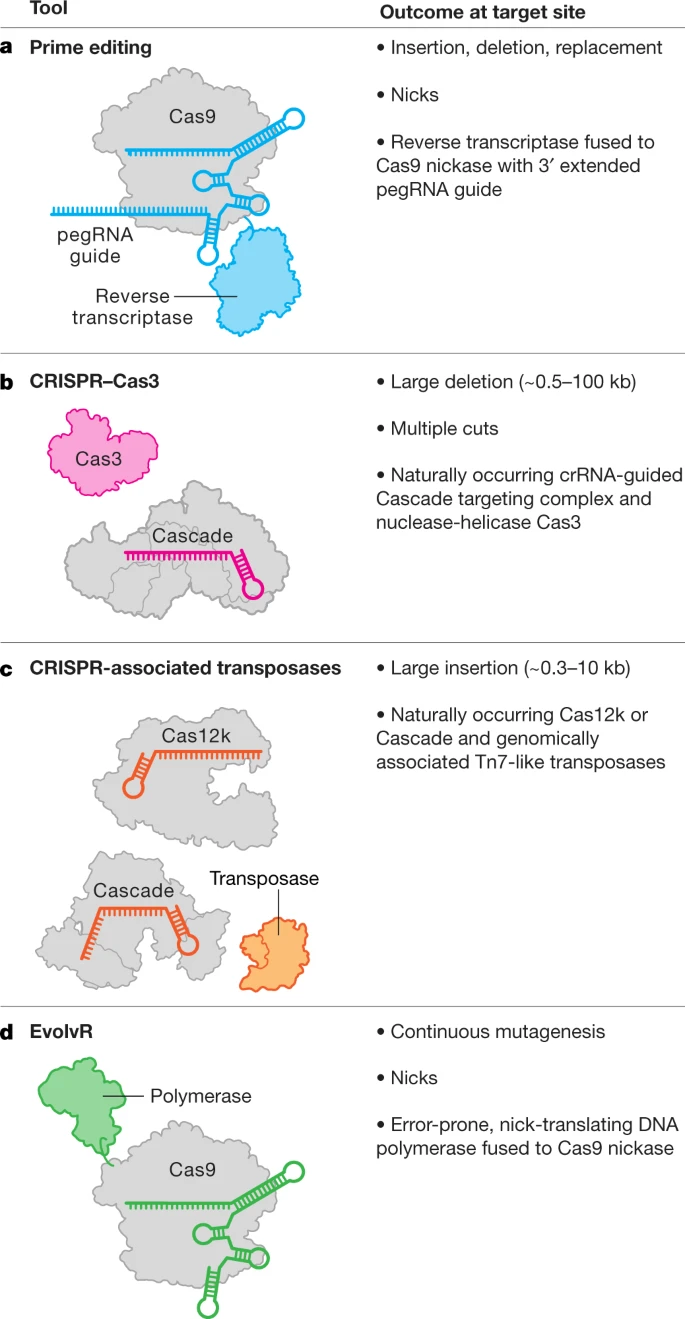

Fig. 3: Emerging tools.

Fig. 4: Editing the human germline.